By Thomas Lundy

“In two decades of travel, doing large expeditions, Pikialasorsuaq was where I most felt like I was on the edge of the planet,” says wildlife ecologist and adventurer Dave Garrow.

In May 2018, Garrow and his fellow mountain adventurers Frank Wolf and John McClelland skied into Pangnirtung, Nunavut, having descended from Baffin Island’s Penny Ice Cap, and noticed something surprising. Dozens of people from the community were on snowmobiles and qamutiiks, heading out of town to hunt, fish and travel. Not towards the 2,000-metre-high ice cap, but in the other direction. Towards the floe edge, where ice and open water meet.

“It opened my eyes,” says Garrow. “I recognized then that the true story of the North is one of sea ice.”

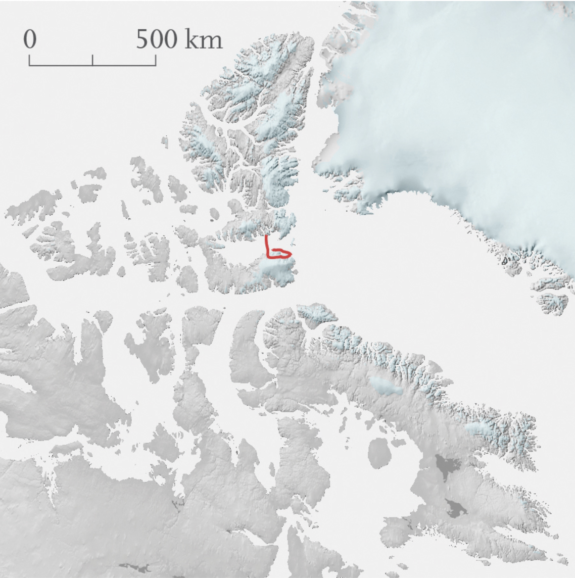

From there, the Pikialasorsuaq Expedition was born. Garrow, Wolf and McClelland set out on May 5, 2022, from Ausuittuq (Grise Fiord), Ellesmere Island, on a 310-kilometre ski traverse aiming to explore, document and research the North Water Polynya, a massive area of open water surrounded by sea ice. The name of the expedition, Pikialasorsuaq, is the Kalaalisut (West Greenlandic) name for the North Water Polynya and translates as “the Great Upwelling.”

“This was really an expedition focused on better understanding sea ice,” says Garrow, “and bringing stories of sea ice and the changes we’re seeing to Canadians.”

Wedged between Umingmak Nuna (Ellesmere Island), Tallurutit (Devon Island) and Greenland in the northern reaches of Baffin Bay, Pikialasorsuaq is the largest polynya in the Arctic. Open year-round, at its peak it spans up to 85,000 square kilometres — about the size of Ireland. It’s an oasis in a frozen desert. Plankton drift in the water column. Shrimp feed on them and are in turn fed on by char and cod. Beluga, bowhead whales and ringed seals peruse the buffet, take their pick, then vanish. Polar bears lurk. This is one of the most biologically productive regions north of the Arctic Circle.

For Garrow and his expedition mates, sea ice was a completely different dynamic to the sturdy glaciers they were accustomed to as experienced mountain travellers.

Terry Noah, Qikiqtaaluk Inuk and operator of outfitting and guide service Ausuittuq Adventures, and his assistant Nolan Kiguktak transported the team from Ausuittuq to Ward Point on the northern coast of Tallurutit. They shared long-held knowledge critical to understanding sea ice conditions, prevailing winds, polar bear travel corridors and how to move safely through their habitat.

In spring, polar bears mostly rest among scattered ice heaves during the day, when Garrow and company would be on the move. Noah and Kiguktak warned them to navigate the larger heaps of ice with caution lest they come face-to-face with a startled bear. But in the heart of polar bear country, encounters of some kind are inevitable.

“Each night after dinner, we’d come out of the tent and have whiskey and some chocolate,” says Garrow. “As we piled out [one night], I glanced over my shoulder. And there, about 50 feet from the camp, was a nine-foot polar bear.” Twenty minutes of curious investigation later, the bear left them to their nightcap, off to find itself a ringed seal or two.

They divided the expedition into three legs: first, sea ice travel from Ward Point to — and then along — Pikialasorsuaq’s edge, before crossing the Devon Ice Cap and exiting via the Sverdrup Glacier. Then, back to Ausuittuq via Cape Hardy and Jones Sound.

Each leg provided its own set of thrills and challenges, but the first

was what Garrow called the technical crux of the expedition — the edge of the polynya.

“When you see images of the floe edge, it’s quite calm,” says Garrow. “People are sitting in lawn chairs, watching whales go by. That wasn’t our experience.”

The team spent a day travelling less than 20 metres from the edge of the polynya, about six kilometres offshore and skiing on a mere 1.2 metres of ice, before retreating satisfied to a safer distance. “There was so much wind that the sea spray was hitting us from 60 feet away, and you could actually see chunks of ice shearing off as the wind grabbed them. It felt like being on the summit of a mountain for far too long.”

Pikialasorsuaq and its surrounding sea ice form a life-supporting and dynamic environment — and an increasingly fragile one. Garrow and his teammates left Pikialasorsuaq with a new perspective and, through storytelling, an aim to bring more Canadian eyes and ears to this vital ecosystem. They saw that the sea ice is changing, becoming increasingly unstable, and it kept them in a state of uncertainty. Yet it was only a glimpse of what is being experienced by the people for whom sea ice has been an infrastructure and an extension of their working land for millennia.